COVID-19 Accelerates Aging Of The Brain And May Lead To Dementia - Research

Posted by Amarachi on Tue 08th Mar, 2022 - tori.ngAccording to a new study, people who have contraced COVID-19 no matter how mild may have accelerated aging of the brain and even increased chances of having dementia or Alzheimer's.

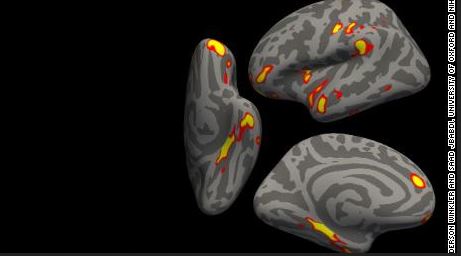

The study, published Monday, March 7, in the journal Nature, is believed to be the largest of its kind and it found that the brains of those who had Covid-19 had a greater loss of grey matter and abnormalities in the brain tissue compared with those who didn't have Covid-19.

The study showed that many of those changes were in the area of the brain related to the sense of smell.

"We were quite surprised to see clear differences in the brain even with mild infection," lead author Gwenaëlle Douaud, an associate professor of neurosciences at the University of Oxford.

Dr Douaud and her colleagues checked brain imaging photos from 401 people who had Covid-19 between March 2020 and April 2021, both before infection and an average of 4½ months after infection.

They compared the results of the 401 people with brain imaging of 384 uninfected people similar in age, socioeconomics and risk factors such as blood pressure and obesity. Of the 401 infected people, 15 had been hospitalized.

Douaud explained that it is normal for people to lose 0.2% to 0.3% of gray matter every year in the memory-related areas of the brain as they age, but in the study evaluation, people who had been infected with the coronavirus lost an additional 0.2% to 2% of tissue compared with those who hadn't been infected, a startling discovery.

In addition to imaging, the study participants were tested for their executive and cognitive function.

Using the Trail Making Test, the participants were tested for cognitive impairments associated with dementia and brain processing speed and function tests. The researchers found that those who had the greatest brain tissue loss also performed the worst on this exam.

"Since the abnormal changes we see in the infected participants' brains might be partly related to their loss of smell, it is possible that recovering it might lead to these brain abnormalities becoming less marked over time. Similarly, it is likely that the harmful effects of the virus (whether direct, or indirect via inflammatory or immune reactions) decrease over time after infection. The best way to find out would be to scan these participants again in one or two years' time," she said.

Douaud added that the researchers anticipate reimaging and testing the participants in one or two years. And while the study finds some association between infection and brain function, it's still not clear why.

The authors cautioned that the findings were only of a moment in time but noted that they "raise the possibility that longer-term consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection might in time contribute to Alzheimer's disease or other forms of dementia."